Home | Join/Donate | Current Voices | Liturgical Calendar | What's New | Affirmation | James Hitchcock's Column | Church Documents | Search

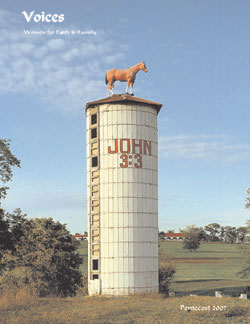

Voices Online Edition -- Vol. XXII, No. 2

Pentecost 2007

Bible Road: Signs of Faith

Photo on Voices cover, Monroe, OH 1992

©Sam Fentress

Jesus answered him and said, “Amen, amen, I say to you, unless a man be born again he cannot enter the Kingdom of Heaven”. John 3:3

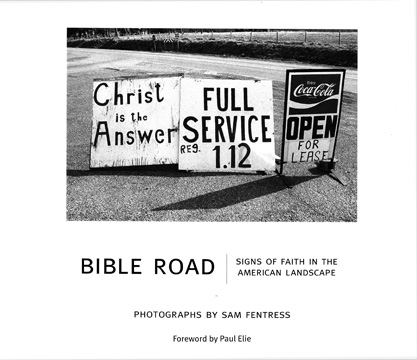

Bible Road: Signs of Faith in the American Landscape

by Sam Fentress

Hardcover: 160 pages. 147 color and black-and-white photographs

Publisher: David & Charles, an imprint of F+W Publications

Price: $29.99

More information at: www.bibleroadbook.com

Photo on cover, Palma, KY 1984

©Sam Fentress

For more than twenty-five years photographer Sam Fentress recorded expressions of religious faith posted along the highways and byways in nearly every part of America. The result of his labor is collected in a book published this March — a book that garnered instant attention from major secular media (e.g., CBS and Newsweek). We interviewed Bible Road’s author/photographer in April. Photos from the book that appear on the cover (front and back) and in the article are reproduced with the author’s kind permission.

Sam Fentress, his wife, Betsy, and their six children live in St. Louis.

Review by Helen Hull Hitchcock

When photographer Sam Fentress drove down Highway 21 in Washington County, Missouri one day in 1981, he had no idea that he was about to launch a project that would span more than two decades, involve travel to every state in the continental US, several exhibits, and the publication this spring of Bible Road: Signs of Faith in the American Landscape.

Along the side of the road near the tiny settlement of Fertile, Missouri, he saw an unusual structure: a life-size figure of Jesus knocking at the “door” of a large red heart, surmounted by the commanding words “Let Me In”. He stopped, backed up his car and photographed it.

Curious, he walked to the nearby house to see who had constructed this unique roadside message. The lady’s name was Hazel Barton. She told the young photographer she had “put it up in case somebody coming around the curve on a Saturday night, maybe drunk, would see it and wonder what’s what and change their life”. At that time, Fentress, who had not yet been baptized, did not know that the image was taken from a verse in the Book of Revelation: “Behold, I stand at the door and knock. If any one hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in to him and eat with him” (Rev. 3:20), a passage often understood to mean that Christ is standing at the door of each person’s heart, waiting to be admitted by an act of faith. Mrs. Barton told him that she had wanted the sign to read, “A latch you must open” — in other words, one must cooperate with the grace Jesus offers. She wanted her son, Norman, to write that on the sign, she explained, “as he was the only one tall enough to do it, but he said there wasn’t room, so he painted ‘Let Me In’ instead”.

Fertile, MO 1981 -- ©Sam Fentress

About ten years after he captured the “Let Me In” sign on film, Fentress drove past the same place, and the sign had fallen down. Now, more than twenty-five years later, it has disappeared altogether.

“After I saw this ‘Let me in’ sign, I started going to some Catholic shrines and grottos to photograph them”, Fentress recounted. Most of these photographs were of sculptural renditions of religious themes, he said. “This was before I was baptized”, he added.

At around the same time, Fentress recalls he started seeing signs that were written messages, rather than sculpted or painted images. Fentress’s brother in Knoxville told him about a man who rode a bicycle with cardboard signs affixed to it with duct tape on which “Acts 2:38” was boldly, if crudely, painted fore and aft. Fentress photographed the unusual bicycle when he was visiting his brother.

The second chapter of Acts records the day of Pentecost, and Peter’s preaching to the Jews. Acts 2:38 says, “And Peter said to them, ‘Repent and be baptized, every one of you, in the name of Jesus Christ, for the forgiveness of your sins; and you shall receive the gift of the Holy Spirit’”. The bike painter added the alternative “or Hell” below the Scripture citation.

Knoxville, TN 1981©Sam Fentress

Some people have commented on the “edginess” of this series of photographs. No clear “point of view” of the photographer is evident, and no commentary or explanation of the images is provided, thus giving a quality of detachment to the book. The photographic medium itself can enhance this “distancing” from the subject in a way that painting or sculpture cannot. The photographs do not impose the photographer’s personal opinion on the subject matter he transmits to us. The book is a “documentary” rather than a subjective interpretation filtered through an artist’s imagination.

“My approach has been to take a hot subject matter and take a cool distanced perspective in presenting the subject”, Fentress said. “There is in the art world a certain acceptance of documentary photography — a cool, distanced look at subject matter that will allow even highly charged subject matter to be presented as it is — whether it’s a war or something that’s very questionable morally or religious. It’s as if to say, ‘here it is, here’s this phenomenon that’s out in the world’, and I’m aware of that effect, and I wanted to make sure that the pictures are a literal rendition of something that is really out there in America”.

Fentress sees a precedent for this aesthetic approach in the British Romantic poet John Keats, who used the phrase “negative capability” to describe this phenomenon of emotional detachment — of the maker of the work being outside the work. (Keats used the phrase “negative capability” in an 1817 letter to describe a state “when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason”.)

Through the intentional open-mindedness of “negative capability”, Keats intended to distance himself from his poems, to have his poetry be separate from himself, rather than a mode of self-expression. James Joyce and T.S. Eliot (whose work Fentress studied and admired in high school and college) used these methods in their own literary works.

“In photographing these Bible road signs, a subject matter that could be handily dismissed by a whole spectrum of non-religious people”, Fentress says, “I deliberately chose a method that is dispassionate, neutral, detached”.

Was there something in his background that contributed to his manner of viewing the “Bible Road” signs?

There was, Fentress says. “Long before I had any idea of doing this Bible signs project, I had come to love Rembrandt’s etchings that had to do with biblical subjects, Dürer, Schongauer, various artists in that time period. And illuminated manuscripts, such as the Trés Riches Heures of the Duc du Berry. I had a deep love for that art, but I was doing nothing about it in my own photography, which tended to be natural and industrial landscapes”. But there was an additional factor. “During this period”, Fentress recalls, “I was also reading a lot of Aquinas, the Bible, Protestant and Catholic theology — sort of on my own ‘road’ that eventually led to Rome”.

He said he was aware of the “modernist minimalist tradition in the 20th century, coming from people like Marcel Duchamp and the Dadaists, of taking a random object — tire, a cup, a urinal, for example — and making it into a work of art by changing its orientation, removing it from its ordinary context, such as by turning it upside down, or on the side, or lining it with fur; forming conundrums of everyday objects to create a new kind of art”.

Such art was deliberately jarring, in order to penetrate the viewer’s preconceived ideas, to present the object in an alien context in order to make the viewer see in a new way. “When I started doing the ‘pilgrimage’ photographs of shrines, and so on, I wasn’t sure how the pictures were working”, the photographer said. “I came to think that [my approach] wasn’t really working. These works were strong as religious sculpture already, and might be of interest to a religious audience; but my pictures weren’t doing anything new with the subject matter that could be of interest to a general audience”.

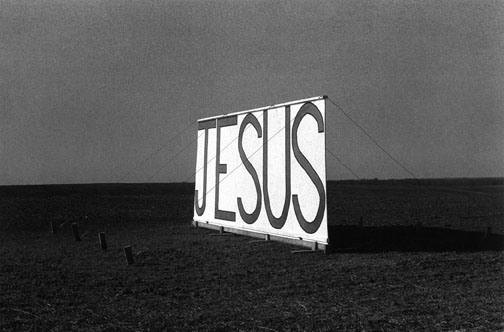

“At the same time I started seeing these roadside messages”, he tells us. “For example, the Jesus sign in a harvested corn field. I was struck with this sign as I drove past — just the stark power of the word JESUS, the holy name, standing alone in a plowed field — on a large sign supported by several small stakes and rather delicate wires. Apparently it was a farmer saying thank you for the bountiful harvest”.

Vergennes, IL 1982 ©Sam Fentress

The sculptural aspect of the black and white photograph of the Jesus sign — the structural simplicity of the lines of the wire, for example, tied in with Fentress’s fascination with the minimalist art work he had been seeing in New York. “Noticing these visual connections with contemporary art, I thought, might help to bridge the gap between contemporary art and Rembrandt”, he said.

As his work on the road signs progressed, the things that started being of greatest interest to Fentress were things that weren’t clearly “art” to begin with — unlike some of the shrines and religious images he’d photographed earlier. “Other things — the words, the messages, the impulse of the sign-makers to express some religious message on whatever is at hand, whether it’s a tree or a truck mud flap or the side of a barn — began to emerge as more interesting to document extensively”, Fentress says. “I gradually became aware of how these road-side messages were employing all different sorts of ways of putting ideas and images in front of the people who traveled along our modern trade routes”.

He explains: “I’m aware that the message of Christianity was spread along the trade routes in early Europe. There was time when all the travelers along the trade routes were people with wagons or pack-horses or ships. In our time, cars — motor vehicles — made a new set of trade routes, and people put up signs and messages along them in much the same way. In the past it might have been missionaries that moved to the trade routes to evangelize. Today, it is the people who live on our own version of trade routes who evangelize the travelers”.

“I love the medieval pilgrimage routes”, he says, “the act of moving through space with a destination, I love the sculptural cycles that narrate events and episodes of Christian history found in the cloisters of monasteries. When I wasn’t in class or going to the print room to look at Rembrandt prints, I spent time looking at the Romanesque sculpture cycles in books in the Chicago Art Institute library”.

Fentress is convinced that “The people who put up the ‘Bible signs’ along the highways and roads, on their dwellings or trees or posts, are also trying to project or ‘sell’ their message — or compete for attention with the highway advertisements for McDonald’s etc. In a way, we can see it as a modern version of the shrines along the pilgrimage routes of the Middle Ages”.

Was there an event or any one image that may have inspired his particular vision or insight? Fentress says there was. “Before I photographed any of these Bible road signs — at least in a purposeful way — I taught for a semester at the University of Arkansas in the spring of 1981. A student brought in a striking black and white photograph of a barn that was painted all over with Bible verses — sixteen years before I photographed it again, as it appears in the book.

Fayetteville, AR 1997 ©Sam Fentress

“At that time I was taking the Confraternity Home Study Service correspondence course on the Catholic faith. I’d read the Bible a couple of times by then, and listened to it on cassette tapes. On Sundays I would go to Mass (I would watch the Mass and say the prayers, but did not take Communion), and I also went to Protestant services.

“The student’s photograph of the barn bowled me over. It gave me ideas. Another student in the class told me about a place called the Christ of the Ozarks in Eureka Springs, in northwest Arkansas. It’s a Protestant shrine, with a huge statue about seven storeys high of Christ with his arms outstretched. They were also trying to build a small-scale replica of Jerusalem when I visited there” he explains.

“The student’s photograph of the barn was what made me interested in doing that — that jarred me into thinking about that”, Fentress explained. “My project of documenting these biblical road signs grows out of both a love of art and a love of the Bible”.

His photographic “pilgrimage journey” would continue seventeen years later when he had a grant from the Bradley foundation to pursue the project: “I got to all states but Hawaii”.

“A certain critical part of that journey had developed first with reading just about everything that Nietzsche wrote” Fentress says, “I had become a relativist through reading Nietzsche, Freud, and Marx; and I thought that with the help of structuralism everything could be explained”. As a college student, he had close Jewish friends, though he recalls that he had never really thought much about the Holocaust until then. This encounter had a profound effect: “The Holocaust blew my worldview out of the water. I knew the Holocaust wasn’t evil as a matter of opinion, but was in fact objectively evil. I had no vocabulary that was available to me for that (for formulating a concept of objective evil or good), so thinking about this led me to take a philosophy of religion class in which Thomas of Aquinas was mentioned. I started reading Plato and Aristotle and the Bible and started to put together a worldview to explain the Holocaust to myself. That sort of started the ball rolling — on a journey that would lead me into the Catholic faith”.

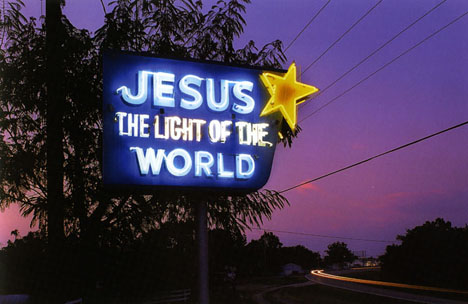

Pittsburgh, KS 1997 ©Sam Fentress

Still, Fentress stresses again, when he started photographing the signs he hadn’t been baptized. Soon after the earliest photographs, he moved to St. Louis in 1981 to teach at Florissant Valley Community College — and his personal pilgrimage paralleled his documentary route.

As taking the pictures progressed, he said, “it was definitely part of my fleshing out of what I was trying to give thanks for — for how art and the Catholic faith and the Bible had all conspired together to give me a coherent world view — and so when I would come across one of these signs I would both be interested in it as a subject for photographic art, and as a possible image to show to another atheist or agnostic as I had been, and perhaps in a certain way draw them to Christianity”.

Was conveying a religious message an objective in the project? Not overtly, the photographer responds. The images must first be an interesting document, Fentress says. Any obvious “religious message” would meet with resistance. The image needs to be aesthetically strong, and the message needs to be subtle enough, he explains, that it may awaken something it the viewer to receive the message — “to go open the Bible”.

“People let their guard down a little because it’s photography”, Fentress comments. “Since it’s a photograph — I didn’t just make it up — it has a certain air of objectivity, documenting something that’s out there. Bible Road is a documentary series, but can also be an aesthetic strategy. If people today look at, say Rembrandt or Grünwald altarpieces, they see an artistic creation” — an artist’s peculiar vision in an expertly painted surface.

“I’ve tried to subvert preconceptions that different audiences would bring to this subject matter”, Fentress says.

He explains that in early exhibits of his photographs of road signs, “people would often comment, ‘that’s not done anymore’, or ‘this is all from the South’, or ‘it’s all Protestant’, or ‘it’s all Bible Belt’, or ‘it’s all poor people’, or whatever — so part of what drove me was a certain stubborn desire to find evidence contrary to that. It’s not just the city or the country, it’s not ‘Red State or ‘Blue State’.”

Lampe, MO 1997 ©Sam Fentress

The pictures in Bible Road shatter such stereotypes. The photographs represent a very broad spectrum of religious, racial and ethnic groups, located in both urban and rural settings in every corner of America — and span nearly a quarter century. These images document a continuing religious vitality unique to America — and could not have been done the same way anywhere else.

The signs tie in with the Constitution, with freedom of speech, Fentress notes. “Sam Harris may want this to go away, but unless he can exert 1984-type control over the country, he should just abandon hope”, Fentress says. (Harris is an outspoken critic of religion, and author of The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Reason 2004-05.)

What do the “Bible road signs” have to do with the author’s Catholic faith?

“Pope Benedict became pope after all of my work was done on this book”, Fentress says. “But his critique of relativism and his desire for Europe to return to its Christian roots really resonates with me, because that’s where I was when I first encountered the signs and began to document them — I was sort of a European relativist from Nashville”.

In the Bible Road book, Sam Fentress lets us see what he saw on his dual journey.

**Women for Faith & Family operates solely on your generous donations!

WFF is a registered 501(c)(3) non-profit organization. Donations are tax deductible.

Voices copyright © 1999-Present Women for Faith & Family. All rights reserved.

PERMISSION GUIDELINES

All material on this web site is copyrighted and may not be copied or reproduced without prior written permission from Women for Faith & Family,except as specified below.

Personal use

Permission is granted to download and/or print out articles for personal use only.

Quotations

Brief quotations (ca 500 words) may be made from the material on this site, in accordance with the “fair use” provisions of copyright law, without prior permission. For these quotations proper attribution must be made of author and WFF + URL (i.e., “Women for Faith & Family – www.wf-f.org.)

Attribution

Generally, all signed articles or graphics must also have the permission of the author. If a text does not have an author byline, Women for Faith & Family should be listed as the author. For example: Women for Faith & Family (St Louis: Women for Faith & Family, 2005 + URL)

Link to Women for Faith & Family web site.

Other web sites are welcome to establish links to www.wf-f.org or to individual pages within our site.

![]() Back to top -- Home -- Back to the Table of Contents

Back to top -- Home -- Back to the Table of Contents

Women for Faith & Family

PO Box 300411

St. Louis, MO 63130

314-863-8385 Phone -- 314-863-5858 Fax -- Email